How does a compressor / limiter work?

What will we cover in this tutorial:

– Controls on a compressor

– How to set up a compressor in practice

A compressor is basically an automated volume control. You set a certain maximum volume and give the compressor instructions to turn it down if it gets louder than that.

An example of how you can use this: If the volume of a sound gets too loud during recording, it will simply start clipping. Put a compressor on it that automatically attenuates the volume just before it starts clipping and you will avoid a lot of problems.

Another example in which you might use a compressor: Suppose your recording has some very loud peaks here and there, but apart from that the rest of the recording level is very low. If you just turn up the volume, those peaks will start clipping. A compressor can attenuate the peaks and turn up the volume of the whole recording after that, making it a little louder.

But besides these practical ways of using a compressor, a nice side effect of it is that you can also color the sound with it. You can make a voice-over sound fuller and fatter with a compressor, or you can give music a little more ‘punch’. Each compressor sounds different. And if you know the sound of a certain compressor, you can choose exactly the right one to make your mix sound better.

In the tutorial ‘Picking the right compressor’ we will discuss the sound of various (very well known) compressors. In this tutorial we will have a look at how to control one. In this video you’ll learn all the basics:

Controls on a compressor

So a compressor (and a limiter as well) is an automated volume control. You set a certain maximum volume and give the compressor instructions to turn down anything that is louder than that.

What that ‘certain maximum volume’ is and how much the sound is going to be attenuated, is something you can control yourself.

Threshold

If the sound gets louder than the threshold you specify here, the compressor will lower the volume of the sound. How much is determined with the Ratio knob.

Ratio

With the Ratio you determine how hard the compressor works. You choose a ratio, for example 3:1 or 5:1. If you select 3:1, the compressor will reduce a signal that is 3 dB higher than the threshold value to 1 dB. On many compressors you will see just ‘5’ instead of 5:1. Or ‘3’ instead of 3:1.

Side note: Compressor or limiter?

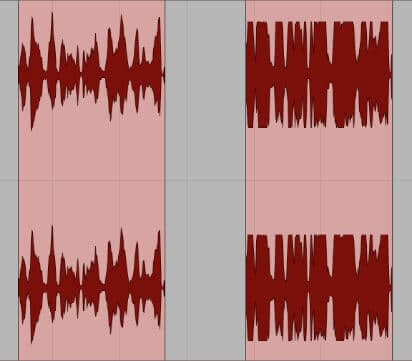

If you select a ratio of 12:1 or more, it’s no longer called compression, but limiting. So a limiter is a compressor with a ratio higher than 12:1. The most aggressive form of limiting is ‘brickwall limiting’, where the ratio is infinite:1. This is useful when the sound is absolutely not allowed to exceed a certain value. It is used a lot to make a mix sound louder: you cannot exceed 0 dBFS (see our ‘Practical(!) audio theory’ tutorial why), so you set the threshold to 0 dBFS and nothing will go wrong. Sounds ideal, but if overused (as was done a lot in the past!) your mix will sound dull, flat and distorted. So use brickwall limiting with care! Below an image of a waveform without brickwall limiting (left) and with heavy brickwall limiting (right). The waveform is ‘flat-topped’ as you can see.

Attack

With the Attack you control how fast the compressor starts working after the audio has passed the threshold. So basically you say to the compressor ‘if the sound goes over the threshold, do nothing during the first few milliseconds. After that, turn down the volume by X (depending on the ratio).’ It sounds like a nice bonus feature to be able to control this, but the attack has a big impact on the sound! It can give just a little more punch if you set a slow attack, for example. Because this leaves the initial peak fully intact. Experiment with slow and fast attack times on a voice recording. If you set the threshold nice and low and the ratio quite high (10:1 for example), you will immediately hear the effect of the attack.

Release

Exactly the opposite of attack. You decide when the compressor stops working. Suppose you set the release to ‘infinite’ (if you could) and a sound exceeds the threshold. The compressor will then turn down the volume of that sound, as it should. But with an infinite release setting, the compressor is instructed to keep it’s settings like this forever. Ok, that’s not very useful. But use milliseconds instead and a subtle change in the release setting does a lot with the sound. If you play a guitar chord for example, with the right release time you can make it sound like the chord has a much longer tail.

Knee

On some compressors you can also control the ‘knee’ settings. You can choose between ‘hard knee’ or ‘soft knee’ or sometimes something in between. Hard knee means that the compressor turns the sound down quite resolutely when it has gone over the threshold. With soft knee it all goes a bit more gradually and the compressor is a bit more friendly and forgiving. The effect of the knee settings is quite subtle however.

(Makeup) Gain

When you have finished tweaking the compressor, this is the last knob you use. We know a compressor lowers the volume of the sound when it gets above a certain threshold. This makes the sound more compact, the loudest peaks are simply turned down. So that means you can turn up the volume without clipping those loudest peaks. And that is what the make-up gain does.

How to set up a compressor in practice

How to you set a compressor? What is the right amount of compression? Well, that depends on what you want.

If we look at music, it’s safe to assume that a rock track will probably need more compression than a classical recording.

In post production there are differences as well. In a short commercial, a healthy amount of compression on the voice-over is common. But in a movie I wouldn’t use that much compression on the actors’ voices. If you take all the dynamics out of the recordings, it doesn’t sound natural anymore and after 1,5 hours of watching it, it’s often tiring for your ears as well.

But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t use compression at all, because it’s also quite annoying when you have to continuously turn the volume up or down during a movie.

If you don’t have much experience with compressors, you can use another production as a reference. How full, dynamic or flat does the vocal or voice-over sound there? Try matching the sound of your vocal or voice-over track with that by playing with the threshold and ratio.

Be sure only to pay attention to the dynamics of the recording, so how compact or how dynamic it sounds. Because the sound is determined by much more things than just compression. And keep it realistic: you can’t make a 16 year old voice-over with a cheerful tone of voice sound like a 62 year old hollywood trailer voice.

Using a compressor is different every time, depending on what you are working on. But the steps you take to get a perfect compressor setting, is more or less the same every time:

– Set the ratio to 3:1. This is only a start setting, we will be tweaking this later on.

– Set the attack between 5-10 milliseconds and the release between 50-60 milliseconds as a starting point.

– Now determine when the compressor starts working with the threshold control. First set it all the way to 0dB (no compression) and then play back the track.

– Slowly pull the theshold level down until the compressor starts working. This can often be seen on a gain reduction meter. And heard, of course! Now it’s a matter of listening what sounds good. If you pull the threshold down too far, you hear that the compressor has to work hard and everything gets dull and lifeless. If you don’t use enough compression, you hear big differences in volume and it will not sound as ‘fat’ as you would like it to sound.

– Then focus on the ratio. With very dynamic audio you might use a higher ratio (3:1 or more), sometimes very subtle compression is enough (1,5:1 or 2:1). For example if you don’t really need compression, but are looking for a certain coloration of the sound. In the tutorial ‘Picking the right compressor’ you can read how a couple of very well known compressors (plugins) color the sound.

– Now try different attack and release settings. Setting the attack too fast will probably sound a bit too ‘aggressive’, everything is immediately compressed which can sound unnatural. Too slow causes the compressor to barely do its job. The wrong release setting sometimes gives a ‘pumping’ sound (the last part of a word or chord is suddenly made louder by the compressor). Try to get an ‘even’ sound with the attack and release times.

– Because the compressor now attenuates all loud peaks in the recording, the total volume also sounds softer. Use the Make-Up Gain to turn up the total volume.

Questions or comments? Let me know via gijs@audiokickstart.com!